Source:

http://www.nature.com/news/365-days-nature-s-10-1.19018?from=groupmessage&isappinstalled=0#rd

Written by: David Cyranoski

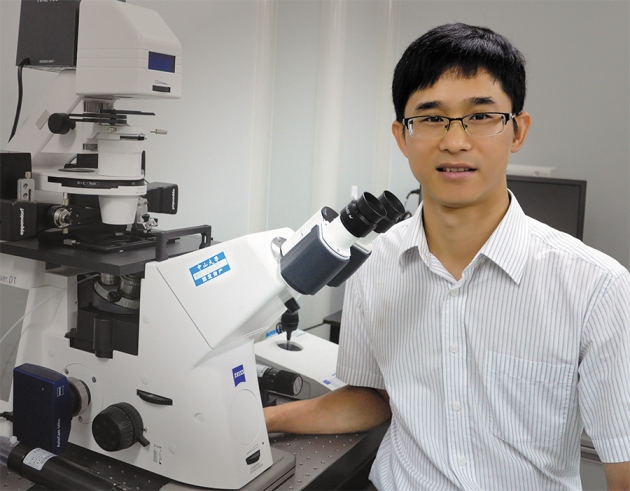

JUNJIU HUANG: Embryo editor

A modest biologist sparked global debate with an experiment to edit the genes of human embryos.

Courtesy Junjiu Huang

Courtesy Junjiu Huang

In April, Junjiu Huang published the world’s first report of human embryos altered by gene editing. The news thrust rapid developments in gene-editing technology into the spotlight and ignited a huge debate about the ethical use of such tools. But Huang, a modest and soft-spoken molecular biologist at Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou, chose to stay out of the limelight.

Huang and his team used a powerful technique known as CRISPR–Cas9, which can be programmed to precisely alter DNA at specific sequences and has swept through biology labs in the past few years. He told

Nature in April that he wanted to edit the genes of embryos because: “It can show genetic problems related to cancer or diabetes, and can be used to study gene function in embryonic development.” In his study, he modified the gene responsible for the blood disorder β-thalassaemia.

Nature

Nature special: CRISPR — the good, the bad and the unknown

Huang used spare embryos — from fertility clinics — that could not progress to a live birth. And he expected his paper, which showed that the process created many unexpected mutations, to steer people away from the technology until it had been proved safe. “We wanted to show our data to the world so people know what really happened with this model,” he said at the time. “We wanted to avoid ethical debate.”

But the opposite happened: the ensuing discussion polarized the scientific community and nucleated several high-powered forums, including an international summit held in December in Washington DC. The general consensus is that gene editing is not yet ready for altering human embryos for reproductive purposes — and there are concerns that it could be adopted prematurely by rogue fertility clinics. Some scientists argue that the technique is permissible for research, whereas others say that this too should be forbidden for fear of a slippery slope.

Huang has been notably absent from the debate, and refused to be interviewed for this article. “Our paper was just basic research, which told people the risk of gene editing,” he wrote in an e-mail. “It’s like he’s hiding,” says Tetsuya Ishii, a bioethicist at Hokkaido University in Sapporo, Japan, who was at the US summit. “That’s strange because there was nothing really ethically problematic about his research. He raised the issue, and that kind of drove discussions on the topic at the summit. That’s a good thing.” But Ishii says that Huang does “have some responsibility to address his critics”, perhaps by discussing cases in which clinical use of gene editing could be worthwhile in the future.

Because of the risks, Huang predicted when his paper was published that it could take 50 or 100 years before the world saw a live-born, gene-edited baby. “But who knows, a decade ago, no one knew of CRISPR,” he said. “We don’t know what will happen.”